While Massachusetts was a hotbed of revolutionary fervor, the island of Nantucket charted a very different course, one guided not by pacifism, diplomacy, and economic survival. During the American Revolution, this small, isolated community became an unusual case of neutrality in a world increasingly defined by sides.

In the 1770s, Nantucket was home to a significant Quaker population, whose religious beliefs emphasized nonviolence and pacifism. These principles led the island to pursue a position of neutrality in the war, a risky decision in an age when loyalty to the Continental or British cause could determine a town’s fate.

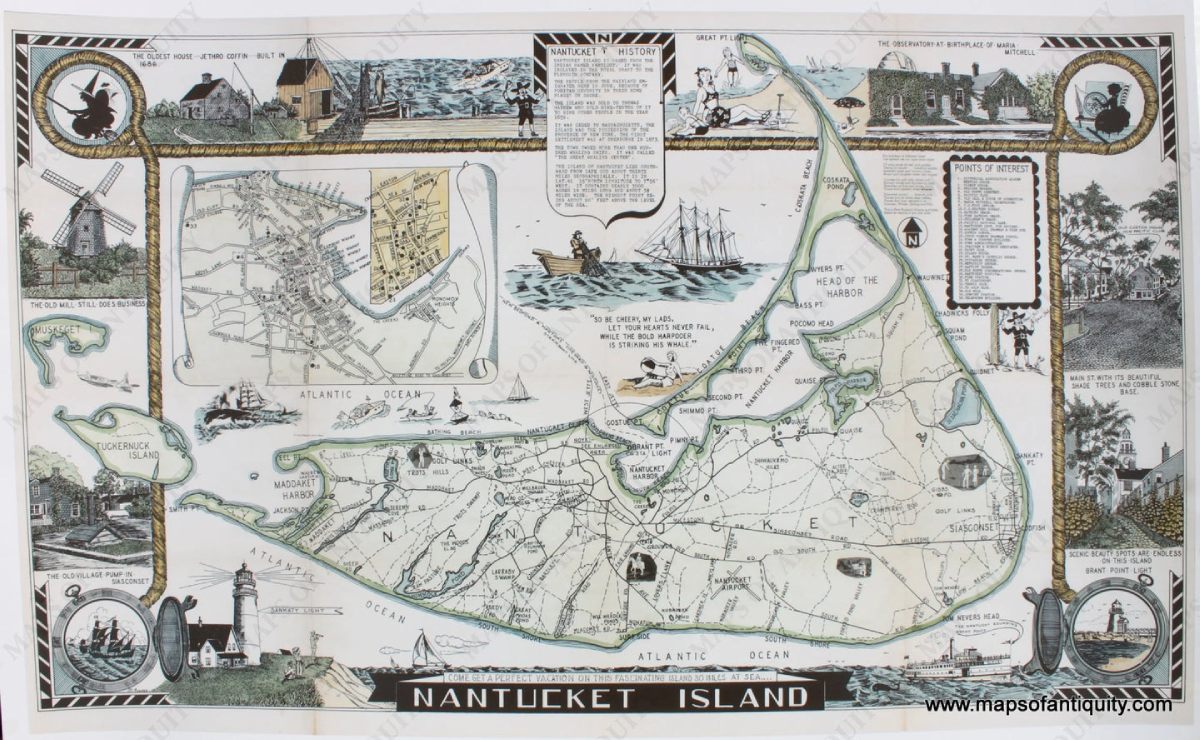

Nantucket’s economy was built almost entirely around whaling. It’s oil-lit lamps in London and lubricated machinery in Europe. With the Revolution disrupting trade routes and both the British and Americans attempting to blockade or control access to essential goods, Nantucket found itself in a precarious position. To maintain trade and avoid ruin, leading citizens engaged in carefully negotiated diplomacy.

Chief among these efforts was William Rotch, a prominent Quaker merchant. Rotch made direct appeals to both the Continental Congress and British authorities to allow Nantucket to continue exporting whale oil, arguing that the island’s survival depended on it. In doing so, he walked a tightrope, seeking exemptions and permissions while insisting on the island’s neutrality. Rotch even met with British officials in Nova Scotia and later in Europe to secure trade channels.

Nantucket’s neutrality, however, was not without controversy. Mainland patriots accused the island of being soft on the British, and American privateers occasionally seized goods from Nantucket ships. At the same time, British commanders recognized the island’s strategic value, particularly its boats and supplies, which threatened its independence.

Despite these pressures, Nantucket avoided direct military conflict, and many residents quietly supported family and friends fighting on the patriot side. Others attempted to stay removed entirely.

When the war ended, Nantucket faced a new reality. Its once-lucrative British markets had evaporated, and the U.S. economy was unstable. Many whalers and merchants, including Rotch himself, would eventually leave the island in search of better opportunities abroad. But Nantucket’s Revolutionary experience remains a unique chapter in the American story, one defined by pragmatism and the strength of conviction.

The legacy of Nantucket’s Revolution-era neutrality reminds us that resistance can take many forms. In a war defined by violence, this small island held fast to its values, proving that courage sometimes lies in restraint and that survival itself can be a revolutionary act.

And while the Revolution tested Nantucket’s resolve, the island’s fortunes would rise again in the 19th century, when it emerged as the whaling capital of the world and a symbol of American maritime enterprise.